As the UK’s human rights sanctions programme marks its first anniversary, how has the government used its new powers? Who has been sanctioned, where and why?

Launched with fanfare one year ago on 6 July 2020, the UK’s Global Human Rights Sanctions regime gave the foreign secretary the ability to sanction persons implicated in human rights abuses anywhere across the globe. Announcing the programme, Dominic Raab asserted, ‘This is a demonstration of Global Britain’s commitment to acting as a force for good in the world’.

Often referred to as ‘Magnitsky sanctions’ in honour of Sergei Magnitsky, the fearless Russian investigator who unmasked large-scale state-tolerated corruption only to end up dead in Russian police custody, the UK sanctions impose asset freezes and travel bans on individuals and entities involved in torture, forced labour or violations of the right to life. The UK’s regime follows similar programmes enacted by the US and Canada in recent years. A separate UK Global Anti-Corruption Sanctions regime followed in April 2021.

A year on, how has the UK Global Human Rights Sanctions regime fared?

A data-driven analysis indicates that a total of 72 individuals and 6 entities have been sanctioned in connection with 11 separate instances of human rights violations. Sanctions against those suspected of involvement in violations of the right to life and the prohibition on torture were significantly more common than sanctions against individuals or entities suspected of involvement in the use of forced labour. The entities sanctioned included military holding companies and public security bureaus. Individuals designated ranged from politicians and military officials to family members of suspected perpetrators and prison doctors.

.

How Many Designations were Made?

The UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) launched the regime with 49 new designations. In the remainder of the year, it made another 29 designations in six different tranches, averaging 6.5 designations per month. This may not, however, indicate the likely rate of future designations. In its initial 49 designations on launch, the UK regime was making up for lost time, sanctioning persons that had largely already been sanctioned by the US. A more useful figure may be the rate of UK designations when the initial tranche is discounted: an average of 2.4 per month. By way of comparison, as of 5 July 2021 the US Global Magnitsky regime had 116 active human rights designations under its parallel regime, which saw its first designations on 21 December 2017, averaging 2.8 designations per month.

Of the entities designated, two are state security bureaus in North Korea, one is a special police unit in Russia, one is a public security bureau in China, and two are military holding companies in Myanmar.

.

Which Countries and Situations were Represented in the Designations?

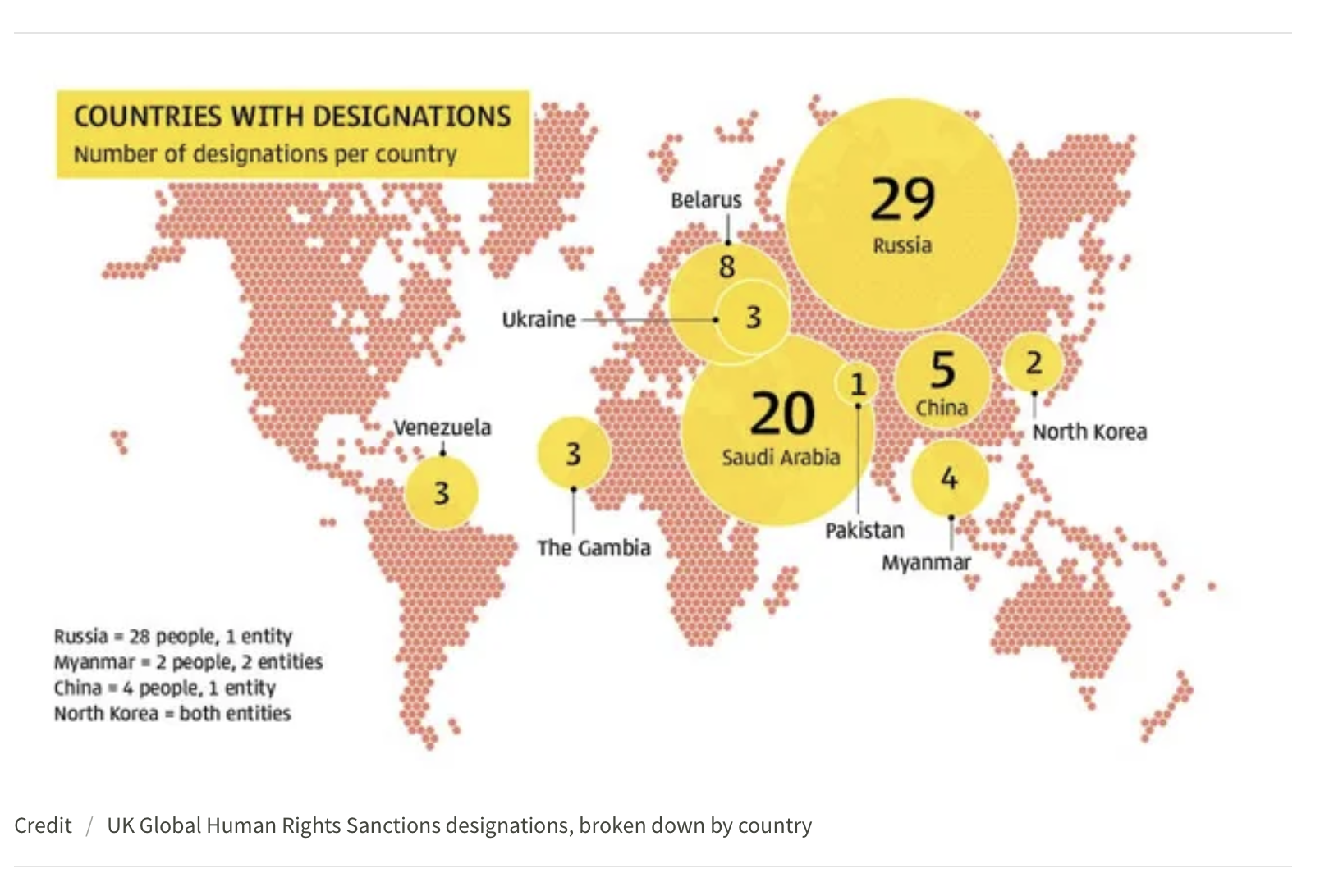

The designations covered five regions, 10 countries and 11 instances of human rights violations.

The largest share of those sanctioned – a total of 29 – are in Russia, followed by Saudi Arabia with 20. The Russia and Saudi Arabia designations were to some extent outliers, with a large number of designations arising from two high-profile instances of human rights violations. A full 25 of Russia’s 29 designations arose from Sergei Magnitsky’s mistreatment and death, and all of Saudi Arabia’s 20 designees were sanctioned for suspected involvement in the 2018 murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi journalist.

The remaining 33 designations covered nine instances of human rights violations, averaging 3.7 designations per case. The nine instances were:

- The Rohingya crisis in Myanmar.

- Torture of the Uyghur population in China.

- Violence against protestors and journalists in Belarus.

- Extrajudicial killings and torture during the Jammeh presidency in The Gambia.

- Police encounter deaths in Pakistan.

- Persecution of the LGBT community in Chechnya, Russia.

- Extrajudicial killings and torture in Venezuela.

- Violence against protestors in Ukraine.

- Murder, torture and slavery in prison camps in North Korea.

.

Which Roles and Seniority Levels were Designated?

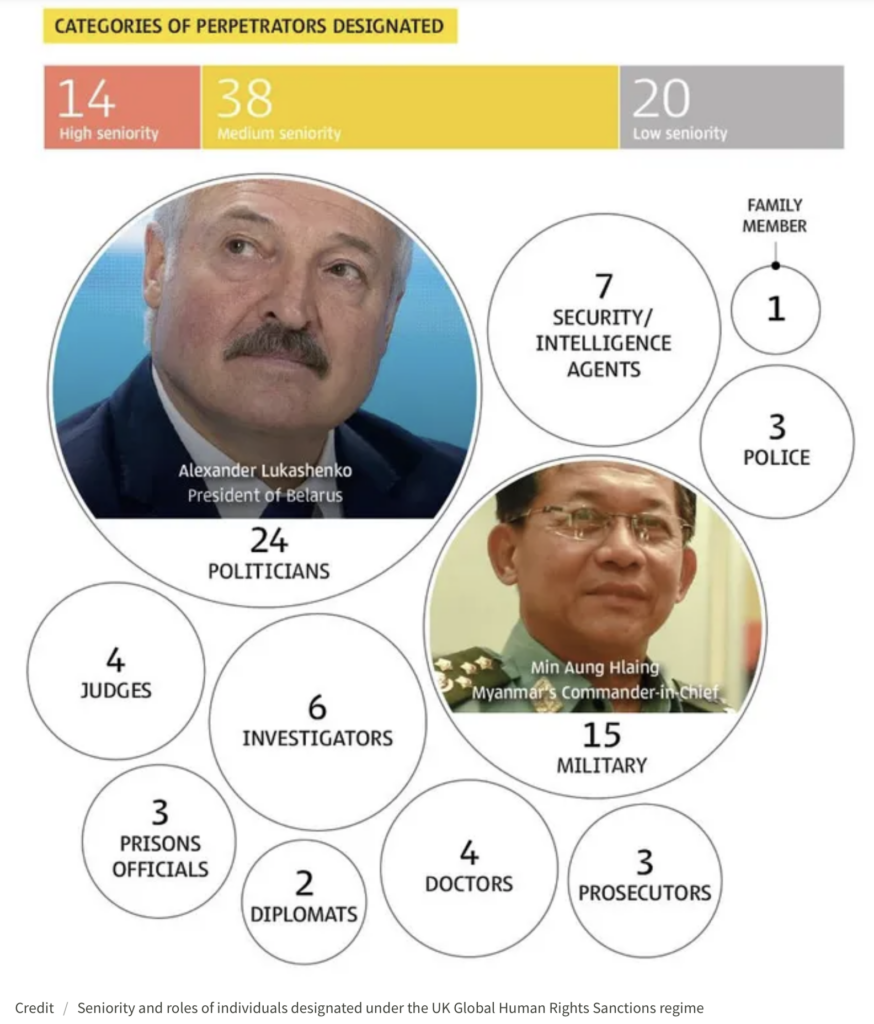

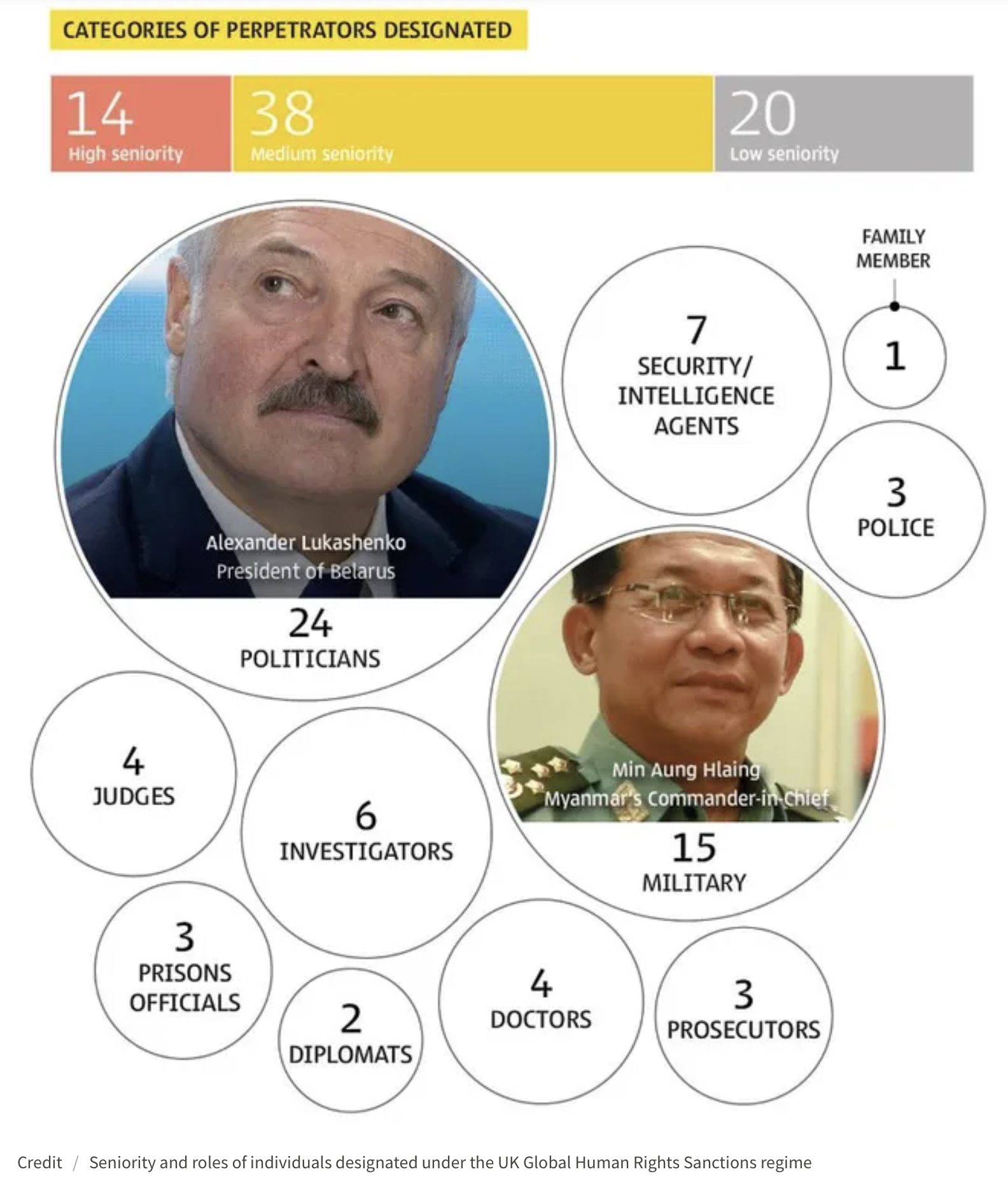

The roles of those designated were wide-ranging. The most common designees were military officials (15) – such as Min Aung Hlaing, Commander-in-Chief of Myanmar’s Armed Forces – and politicians (24), including two current or former heads of state – such as President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus.

Less common roles included one family member: the former first lady of Gambia, Zineb Jammeh, was sanctioned for her association with former President Yahya Jammeh and covering up the illicit transfer of funds. Three Russian doctors were sanctioned for their role in Sergei Magnitsky’s mistreatment, including failure to provide adequate medical care. And a Prosecutor-General in Ukraine was sanctioned for his office’s suspected failure to adequately investigate torture and illegal use of force by Ukrainian law enforcement.

While the FCDO noted in its policy paper on designations that it is ‘likely to give particular attention to non-state actors’, all Global Human Rights Sanctions designations in the first year related to violations by state officials.

In the same policy paper, the FCDO lists ‘the status and connections of the involved person’ as a relevant factor in determining whom to designate. This takes into account the seniority of the person in relevant organisational hierarchies, along with other factors such as any particular links to the UK. Of the individuals designated, 14 were high seniority, 38 were medium seniority and 20 were low seniority.

Over half the mid-level and all the low-level designees were in the Magnitsky and Khashoggi tranches. Outside of the Magnitsky and Khashoggi tranches there were 12 high-level, 15 mid-level and no low-level individuals designated.

.

Which Rights were Violated?

CreditRights violations giving rise to UK Global Human Rights Sanctions designations

.

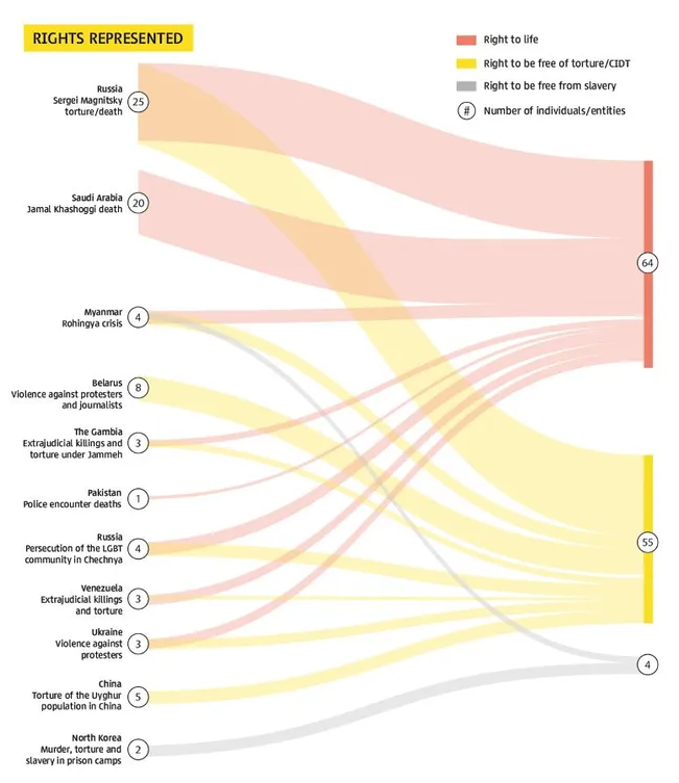

The FCDO can designate under the Global Human Rights Sanctions regime for violations of three rights: (a) the right to life; (b) the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (CIDT); and (c) the right to be free from slavery and forced labour.

Of the 11 instances of human rights violations represented and the 78 individuals or entities designated, there was a heavy skew towards those that implicated the right to life and the right to be free from torture and CIDT. Slightly more individuals and entities were implicated under the right to life (59 individuals and five entities) as opposed to the right to be free from torture and CIDT (49 individuals and six entities). Only four designations (two individuals and two entities) were for violations of the right to be free from slavery and forced labour.

.

Looking Forward

Key questions for the second year of the UK’s Global Human Rights Sanctions regime include: will the momentum of the first year be maintained and built on now that the UK regime has made up for lost time? How will the parallel anti-corruption sanctions regime, launched in April 2021, fare?

There are also larger questions about the regime’s wider impact. Will the sanctions have their desired effect in ending ongoing violations and deterring future abuses? How will the UK government respond if arbitrary counter-sanctions, already imposed by China, are adopted by other countries? Will international coordination increase as mooted new regimes in Japan, Australia and elsewhere come online? And what impact will the UK’s desire to strike trade deals around the world have on its willingness to deploy sanctions? The next 12 months will provide a more accurate picture of the UK’s sanctions ambition.

.

By Charlie Loudon and Celeste Kmiotek, July 20, 2021, Published on RUSI