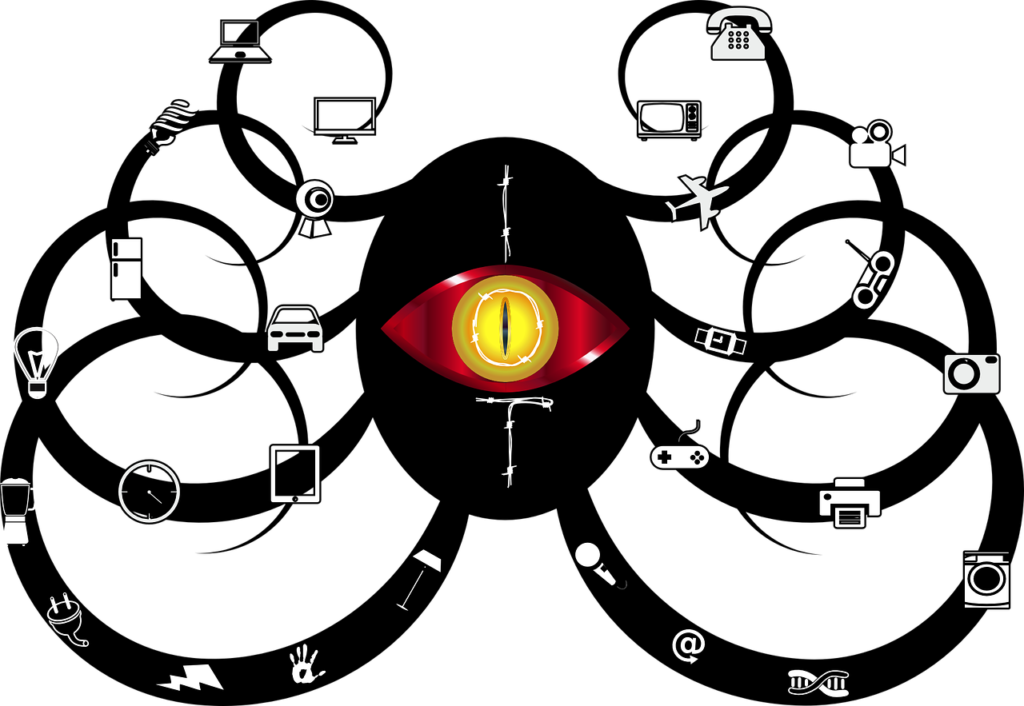

A budding group of venture capital firms and investors are working with the CIA and other U.S. intelligence and military agencies in an attempt to help shape the future of Silicon Valley, ensuring companies produce innovations useful for national security while avoiding funding from potential adversaries like China.

Call it the new world of “spooky finance.”

These firms — like New North Ventures, Harpoon, Scout Ventures, and Razor’s Edge — are often themselves staffed by former U.S. intelligence and military officials, and sometimes work together to cofund national-security-related startups in areas such as artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and next-generation communications.

The new world of “spooky finance” reveals an increasingly tight relationship between venture capital firms and U.S. spy and military agencies, which have long sought to tap into Silicon Valley’s technology base.

“What you’re seeing, and it’s basically been developing over time, is an ‘intelligence-industrial base,’” says Ronald Marks, a visiting professor at George Mason University and a former CIA officer.

“You had a military-industrial base before — now, you’ve got an intelligence-industrial base,” says Marks. “Why? Because, let’s face it: All the intel stufftogether now is, like, 86 billion dollars. It’s the third-largest part of the discretionary budget of the United States. That’s a lot of money; that’s a Fortune 100 company.”

Greater coordination between Silicon Valley and Washington’s national security bureaucracies is much needed, according to Heather Richman, founder of the Defense Investor Network, a Silicon Valley-based group that connects senior officials from the Pentagon and U.S. intelligence agencies with venture capital firms and startups doing work with national security applications.

The Defense Investor Network is focused on “educating investors to stop taking Chinese money and be more transparent about who their LPs [limited partners] are,” says Richman. “We’re trying to get to investors and the companies before this becomes an issue.”

Richman has also pulled together a network of private investors who work together to try to weed out any “nefarious or adversarial ownership” from foreign countries — particularly hidden Chinese investment — before providing financial backing to the startups, she says.

“We call it ‘cap [capitalization] table exorcism’ — we’re actually going in there and removing people on boards and buying them out,” says Richman.

Inevitably, investors have followed the money. The Defense Investor Network has members from all the countries within the Five Eyes intelligence alliance — the U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada, and New Zealand — and includes a former Australian prime minister, as well as behemoths from the Silicon Valley venture capital world, Including Greylock

Partners and Andreessen Horowitz, as well as smaller dual-use venture firms and family offices, according to Richman.

“I feel like it’s every week I hear about two more [dual-use-focused venture capital funds] being launched, which is awesome,” Richman says.

In some instances, the dual-use-focused firms leverage their connections within the U.S. intelligence community to procure contracts for the companies they fund, since the firms’ employees have an insider’s understanding of the technology gaps that the agencies are racing to close.

“The side door or the back door” to the intelligence agencies “is where all the big stuff, and the stuff that’s most important, really happens” when it comes to technology, says Brett Davis, a partner at New North Ventures, a national security-focused venture capital fund, who spent 34 years in the CIA and special operations world.

If it’s a technology priority for them, intelligence agencies are willing to cut through the red tape. “CIA totally gets it and is comfortable working with private industry and has a lot of authorities to do fast contracting, small teams, due diligence, and get contracts in place,” says Davis.

While the startups are receiving contracts within the classified realm, intelligence and military agencies understand that the companies will convert some of the lessons they’ve learned within the government into their commercial technologies, according to Davis. Intelligence and military agencies will also co-locate personnel and other resources with employees from these startups, which can give the tech companies a leg up.

“You’re able to outpace the commercial competition, because you’re working on the hardest issues that CIA and JSOC are working on,” says Davis, referring to the military’s Joint Special Operations Command. “So the company is benefiting along the way, and the CIA and JSOC, they want to be able to defray some of their costs by these companies doing stuff in the commercial world.”

Sometimes, the dual-use-oriented firms will identify military or intelligence applications for a startup’s products, of which the company didn’t even conceive, according to Larsen Jensen, a co-founder of Harpoon and a former Navy SEAL.

“We help to educate founders and their boards in terms of the scope and opportunity in the federal market, and not just in the national security setting,” says Jensen, whose firm has helped secure contracts for companies it funds at Special Operations Command, the Air Force, Space Force, and Veterans Affairs.

The big data analytics firm Palantir serves as a model for some in the “spooky finance” world. In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s own venture fund for emerging technologies, was an early investor in Palantir, a software firm founded in 2003 by Peter Thiel and Alex Karp. In-Q-Tel has long sought to market its products to spy and military agencies and big business alike. Palantir went public in 2020 with an initial valuation of about $22 billion, although it continues to face scrutiny over its appraisal.

“Palantir is the 800-pound gorilla,” says Davis. “That’s the company that opened everybody’s eyes” to the potential value of dual-use-oriented startups.

“Those of us on the intel side, we were like, ‘This is completely intuitive and obvious.’” says Davis. “People said, ‘This came out of nowhere,’ and we were like, ‘No, it didn’t.”

Relations between Silicon Valley and U.S. spy agencies have come a long way since the 2013 Snowden disclosures, when many tech firms tried to create as much distance as possible — at least publicly — from Washington, according to Marks, the former CIA official.

“As they’ve grown older, they see [government] as an opportunity; it’s ‘We gotta work with these guys,’” says Marks. Tech firms realized, he says, “‘F*** you’ is not a policy, it’s the start of a barroom fight.”

U.S. spy agencies have coveted new technologies for decades. But many intelligence officials now believe advances in technology are fundamentally altering the practice of spying.

The push to give the U.S. a tech-generated espionage edge has become a key CIA priority under the directorship of Bill Burns. In October, Burns announced that the agency was creating a “Transnational and Technology Mission Center” to “address global issues critical to U.S. competitiveness — including new and emerging technologies, economic security, climate change, and global health.”

Burns’s announcement follows the standing up in 2020 of CIA Labs, which created an “in-house research and development arm” within CIA, designed to encourage agency employees to collaborate with academics and private sector researchers on emerging technologies.

The CIA has long kept a finger in Silicon Valley with In-Q-Tel, but in 2015, the Pentagon founded the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), which also tries to identify and fund technologies with uses in the national security space. Since then, roughly half a dozen other specialized units within the Pentagon have sprung up to ostensibly circumvent bureaucracy and fund technological innovation.

But the national security-focused venture capital firms — with their access to greater, unconstrained resources — may be able to leapfrog even these government-backed attempts to slash red tape, according to its boosters.

And this symbiotic relationship between the U.S. national security apparatus and finance may evolve into a de facto sort of industrial policy, something traditionally considered anathema to U.S. free-market principles but garnering increasing bipartisan support because of China’s perceived advantages in government-backed research and development.

This was a driving force behind the creation of the Defense Investor Network, according to Richman. The network “brings together a trusted community — these two worlds [of U.S. national security agencies and venture capital] have to start working in lockstep together,” says Richman, or the U.S. will risk being overtaken by China in the technological arms race.

“The metrics are saying that within the last 8 to 10 years there are over 3,000 companies within the top five areas of national security that have significant Chinese investment, because that’s what they’ve targeted,” says Richman. “Can I remove Chinese capital from 3,000 companies? No. Can I take out the top five [companies] and [focus on them] over the next six months? Yes I can.”

Some national security-focused tech startups are keenly aware of the great power dynamics surrounding their work.

“In the U.S., we’re kind of evolving toward a whole-of-nation approach to economics and national security, which is something I would argue the Chinese and Israelis have aggressively embraced in the last decade and are significantly ahead of us,” says Steven Witt, the co-founder of Anno.Ai, an artificial intelligence startup, and a former CIA official. (Anno.Ai has received funding from New North Ventures and Scout Ventures, among other firms.)

Anno.Ai’s “genesis was a CIA program about four or five years ago,” says Witt. A group of former agency officials realized that, contrary to conventional wisdom, they had leapfrogged private industry on some artificial-intelligence-related capabilities while they were at the CIA, and believed they could take these insights and apply them commercially, according to Witt.

Startups like Anno.Ai market their products to the national security bureaucracy and businesses alike. The same AI programs that can help filter and interpret data for Pentagon agencies can be used to, say, analyze economic activity at a granular level within urban areas for real estate firms, according to Witt, who says the company currently has clients in this space. (On the government side, Anno.Ai is under contract with the Air Force; Witt declined to discuss the company’s other federal clients.)

“With the war on terror and investments we made over the last 20 years, we deployed so many sensors all over the world that are collecting tremendous amounts of data. If we hired every single U.S. citizen, we still wouldn’t be able to process all that data in a timely manner,” says Witt. “So building these machine learning algorithms out is helping identify things of interest while they’re still relevant.”

Anno.Ai is working on something called “multi-modal sensor fusion” — essentially, the development of machine learning programs that can collect and interpret data across a wide range of platforms simultaneously, with the different sensors teaching each other to recognize patterns and objects.

“In the machine learning space today there’s a lot of focus on video camera data, but [that’s a] really a human-centric view of the world,” says Witt. “In reality there are so many kinds of sensor types that can take advantage of machine learning capabilities, like acoustic, radar, lidar, hyperspectral, biological” and others. Anno.Ai is currently experimenting with roughly three dozen sensor types, according to Witt.

So the same technology that may be used to understand anomalies in foot traffic in a city’s downtown for real estate valuation purposes could, in theory, also be contracted out by a three-letter government agency to analyze patterns of activity in another country that point to an illicit nuclear program.

The focus of startups like Anno.Ai on appealing both to government and private businesses underscores a fundamental dynamic within the “spooky finance” sector: These startups, and the venture firms and investors who fund them, are designed to make money. Supporters see it as part of a larger wave of “impact investing” — in areas like climate change and energy — that evangelizes the idea that investors can do well while doing good.

“It’s a low bar” for investors, says Richman. “I’m asking them not to do bad for their country” by directing their funding away from companies with sketchy, and often hidden, foreign investment, and toward startups with a clean bill of health, she says. “I’m trying to shame them into acting appropriately.”

Richman believes that coordinating or nudging private investment toward the Pentagon’s or intelligence agencies’ priorities represents a necessary evolution in the relationship between the private sector and government.

“We need to be building defense capabilities outside the Department of Defense,” says Richman. “So if there’s a situation where it should be something solved by the private capital markets, let’s do that; let’s enable that.”

.

By Zach Dorfman, November 4, 2021, Published on Yahoo news