Banksy, the elusive British street artist, built a global reputation creating subversive works that stick a thumb in the eye of the establishment. A screenprint portrays a crucified Jesus holding shopping bags. Another shows paintings up for sale: “I Can’t Believe You Morons Actually Buy This Shit,” reads one. Banksy later rigged a frame to shred a painting — which happened immediately after it sold for $1.4 million.

But even as Banksy’s art rebukes consumer culture and capitalism, it has been swept up into a parallel financial system that many experts say represents the worst of what his art often critiques.

Leaked documents show that, beginning in 2009, London financial broker Maurizio Fabris used an offshore trust to buy more than a dozen Banksy pieces, including several that are now iconic: a rendition of “Girl with Balloon,” “Flower Thrower” and two versions of “Rude Copper,” which portrays a police officer giving the middle finger to the viewer.

Fabris signed a contract with the trust managers, Asiaciti Trust, that allowed him to display the art at home, at no cost. When a trust becomes the legal owner of assets, the collector may be able to avoid or defer taxes on wealth, estate and capital gains.

The Pandora Papers show how several iconic Banksy artworks were bought using an offshore trust in New Zealand. Image: ICIJ

.

Fabris’ trust later sold three of the Banksy works to a London gallery managed by Banksy’s former agent, while the broker and his business associates came under criminal investigation in Italy for alleged tax fraud.

“It’s terribly ironic,” said John Zarobell, a San Francisco University associate professor and author of “Art and the Global Economy.” Banksy’s work “attacks not only authority but the political and economic structures that undergird the art world. But when you become a famous artist, like Banksy has, your work gains lots of value, and then it can become a tool in these kinds of schemes by the ultra wealthy, in order to hide their wealth.”

The records detailing the Banksy transactions are found in the Pandora Papers, a huge cache of documents that describe financial holdings of hundreds of politicians, oligarchs, business tycoons and criminals. Art has become an increasingly popular store of value in the offshore world, the documents show, with pieces traded by shell companies and trusts whose ultimate ownership is often hidden from authorities and the public.

Russian “unofficial minister of propaganda” Konstantin Ernst and the husband of a member of Sri Lanka’s ruling family owned art collections worth millions of dollars through offshore trusts, the leaked files show. An indicted trader in Khmer antiquities held money and ancient relics through a trust in the British Virgin Islands. A Belgian art gallery owner used a Hong Kong company to trade Picassos and Warhols, the records show.

All told, ICIJ identified more than 1,600 works of art by about 400 artists from all over the world, secretly traded through shell companies in tax havens.

Some of the works are on display in homes or galleries. Others are stashed away behind locked doors in freeports — ultra-safe and tax-free warehouses where artworks are stored for years, no more accessible to the public than the gold in the basement of a central bank.

“In a way, we could consider those artworks to be somehow ‘lost art,’ as they will potentially never see the light of the day,” said Maria Nizzero, a researcher at the Centre for Financial Crime & Security Studies in London. “While art has increasingly become a commodity, and we should appreciate its trade value, it is also something that was created to be seen, enjoyed, stimulate emotions and thinking.”

The ease with which art can be traded in secret has attracted criminals, as well. In much of the world, including the U.S., art dealers are not subject to know-your-customer rules meant to stop money laundering and financial crime.

While the European Union and the United Kingdom have recently added art dealers and auctioneers to the list of professionals required to vet their clients and the source of their money, enforcement remains a problem, experts say.

Through his lawyer, Fabris said that he declared all his offshore holdings to the British authorities and paid taxes in the U.K., where he resides. The trust was “never used for tax purposes,” his lawyer wrote.

He added that Fabris chose Banksy’s works “for the artist’s ability to deal with socio-political themes with extraordinary effectiveness.”

Banksy didn’t respond to ICIJ’s requests for comments.

.

In Banksy we trust

The British-born Fabris, a former car racer and now a partner at a classic car investment fund, co-founded Enigma Securities in 2004 in London. Enigma, an investment brokerage firm, had outposts in Milan, Malta and Dubai.

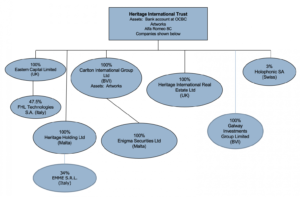

In 2008, Fabris established the Heritage International Trust in New Zealand with the help of Asiaciti, a Singapore-based financial service provider whose internal documents are among those in the Pandora Papers leak. Trusts are commonly used to protect assets or reduce taxes by transferring legal ownership of the assets ー stocks, cash, real estate ー to another party, often a professional firm such as Asiaciti.

At the time, New Zealand offered anonymity and tax exemptions to foreigners who established trusts there. It didn’t require trust managers like Asiaciti to disclose a trust’s real owners or what it held.

A 2015 document from the Pandora Papers shows the ownership structure of Heritage International Trust, established by Maurizio Fabris. Image: ICIJ

.

A chart of Fabris’ offshore holdings and other leaked records reveal that he used the New Zealand trust to buy two luxury cars ー a Ferrari and an Alfa Romeo ー, invest in an Italian firm that patented automotive technologies, and hold shares in shell companies registered in the British Virgin Islands, the Marshall Islands and Switzerland.

Fabris, who described himself in a recent newspaper interview as “an entrepreneur with a passion for architecture and design,” used the shell companies to buy property and to hold shares in the Maltese affiliate of his Enigma brokerage firm.

In 2009, Fabris’ trust paid about $750,000 for 12 Banksy works, including a copper rendition of “Girl with Balloon.”

Banksy often produces multiple versions of the same subject using a variety of media, from traditional canvases to murals. One of the certificates of authenticity accompanying the artwork included hand-written letters by two people who said they personally met the mysterious artist during his 2002 visit to Los Angeles. “I met him and we talked about what was going on in the world and he was very kind and interesting,” one letter said.

The leaked records include drafts of license agreements in which Fabris’ own trust gives him the right to display the Banksy artworks in his homes in Milan, London, Ibiza and the Italian Alpine resort of Courmayeur.

Experts said that such an arrangement may reinforce the illusion that the art belongs to someone else, and protect it from creditors or law enforcement authorities.

.

Under investigation

In 2011, investigators with the Italian securities regulator followed up on anonymous complaints about possible irregularities at the Milan branch of Fabris’ brokerage firm.

In particular, the officials were interested in the firm’s dealings on behalf of a notable client, the Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) bank at the center of an alleged $64.5 million fraud scandal.

Financial police searched Enigma’s Milan office, seizing all the available documentation with details on more than 5,000 trades completed between 2005 through 2008. Fabris cooperated with authorities, court records say.

In late 2012, Fabris’ trust managers sold the copper rendition of “Girl with Balloon” and then two other Banksy pieces for $423,000, recording a $91,000 overall profit. They also sold a Milan apartment and transferred the proceeds to Fabris.

Pieces by Banksy were on display at an exhibit in Rome, Italy, on Jan. 4, 2022. Image: ICIJ/Scilla Alecci

.

The broker was charged with tax evasion in 2015, after which Asiaciti transferred ownership of a dozen pieces of art held in the trust back to Fabris. The firm then helped him wind down his BVI and U.K. shell companies.

The leaked records show that more than $2.5 million in euros and pounds flowed in and out of the trust’s bank accounts in the years leading up to a 2017 trial.

Seven of the pieces transferred to Fabris were by Banksy. One had a simple message painted in capital letters on steel: “Abandon Hope.” It’s not clear whether Fabris still owns them.

Steve Lazarides, the gallery owner, didn’t respond to ICIJ’s repeated requests for comment. At the time, the gallery had no legal obligation to conduct due diligence on the seller.

Asiaciti declined to comment on its work for Fabris.

In a statement to ICIJ last September, the firm said it maintains “strong” anti-money laundering policies and complies with the law in the jurisdictions where it operates. “No compliance program is infallible – and when an issue is identified, we take necessary steps with regard to the client engagement and make the appropriate notifications to regulatory agencies,” the firm said.

In 2017, a Milan court found Fabris and two Enigma co-founders guilty of evading about $6.6 million in Italian taxes and collaborating with an international criminal network, and sentenced them to more than three years in prison. A year later, an appeals court dismissed the international collaboration conviction and overturned the verdict, declaring that the tax crime had occurred outside the statute of limitations.

In his response to ICIJ, Fabris said that “the court case, in addition to causing obvious reputational damages also in the country where he lives, had very serious economic consequences, which forced him, among other things, to give away several properties and artworks.”

.

‘The largest, legal unregulated industry’

Over the last three decades, the global art market has boomed, evolving from a niche sector for the elite into an estimated $50 billion industry.

The transformation brought with it financial crime risks but, unlike luxury real estate, the art market remained unsupervised, experts said, despite anti-money laundering advocates’ calls for a global overhaul. A veteran New York state legislator once called the market a “carbuncle of distortion.”

In 2016, the Panama Papers showed how the use of art for illicit purposes had become a widespread phenomenon. ICIJ and its media partners exposed a trader’s secret multimillion-dollar deals in partnership with a prominent auction house, an ultra-wealthy tycoon shielding his art collection from his estranged wife, and a New York family accused of using shell companies to hide ownership of artworks stolen by the Nazis.

Authorities took notice. In 2018, the European Union amended an existing anti-money laundering directive, adding art dealers and auctioneers to the list of professionals required to verify the identity and source of funds and wealth of a client before entering into a cash transaction worth more than $11,100. If the dealer considers the transaction suspicious, they must report it to the authorities.

EU member states and the U.K. implemented the directive according to their national legal systems, leading to what some experts consider a patchwork of laws.

The U.S., with its $21 billion art trade, the world’s largest, still hasn’t adopted many of the recommendations.

In 2020, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released a report labeling the art industry “the largest, legal unregulated industry in the United States” after investigators linked transactions involving high-value art to sanctioned Russian oligarchs

“Secrecy, anonymity, and a lack of regulation create an environment ripe for laundering money and evading sanctions,” said the report, which cited ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation

In the aftermath, the U.S. revised anti-money laundering regulations, adding antiquities dealers to a list of institutions required to vet clients and report suspicious transactions. Art dealers and traders were not included.

“Girl with Balloon” was on display at a Banksy art exhibit in Rome on Jan. 4, 2022. Image: ICIJ/Scilla Alecci

.

‘The power of money’

On a recent morning, Francesca del Re, a nurse, took her five-year-old son Michele to see a Banksy exhibit with 250 artworks displayed in a historic building in central Rome.

Del Re said she loves Banksy because the artist deals with important themes like politics and the environment and “is close to all of us.”

She was particularly touched when in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the artist made a mural portraying a nurse as a superhero, she said. At the time, del Re was taking care of coronavirus patients in one of Italy’s worst-hit areas.

“I don’t like the idea that his works are marketed and exploited,” she said. “But unfortunately this is the power of money.”

Contributing reporters: Paolo Biondani, Lars Bové, Delphine Reuter and Karrie Kehoe.

.

January 28, 2022, published on The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists