Could TikTok be a ticking time bomb as disinformation spreads across the continent? The Africa Report uncovers multiple attempts to push lies and false narratives ahead of the 2024 elections in Ghana.

With a median age of 18 and 60% of the population under 25, Africa is a continent of ‘digital natives’ with galloping rates of smartphone adoption. In 2022, more than 385 million Africans used social media (27% of the total population) and the figure grows daily. By 2030, three-quarters of Africans are projected to become internet users.

Political challengers to the status quo, like Bobi Wine in Uganda and Peter Obi in Nigeria, have adapted to this new environment, targeting their country’s youth populations to spread their messages on social media networks, which provide an ever more accurate gauge of voters’ preoccupations and preferences.

On the flip side, social media also offers a quasi-anarchic platform that can easily be commandeered for disinformation.

Breaching guidelines

In the context of the war in Ukraine and the presence of Moscow-linked Wagner Group mercenaries in Africa, Russia has been the leader in pushing false narratives on the continent. According to the US government’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Russia has “pioneered a model of disinformation to gain political influence in Africa that is now being replicated by other actors across the continent”.

Not all of these actors are foreign. The Africa Report conducted an in-depth investigation into the use of social media to spread disinformation in Ghana, ahead of the country’s 2024 general election.

In today’s heavily siloed news environment, younger people are ditching traditional analogue and even digital information sources for social networks.

..

..

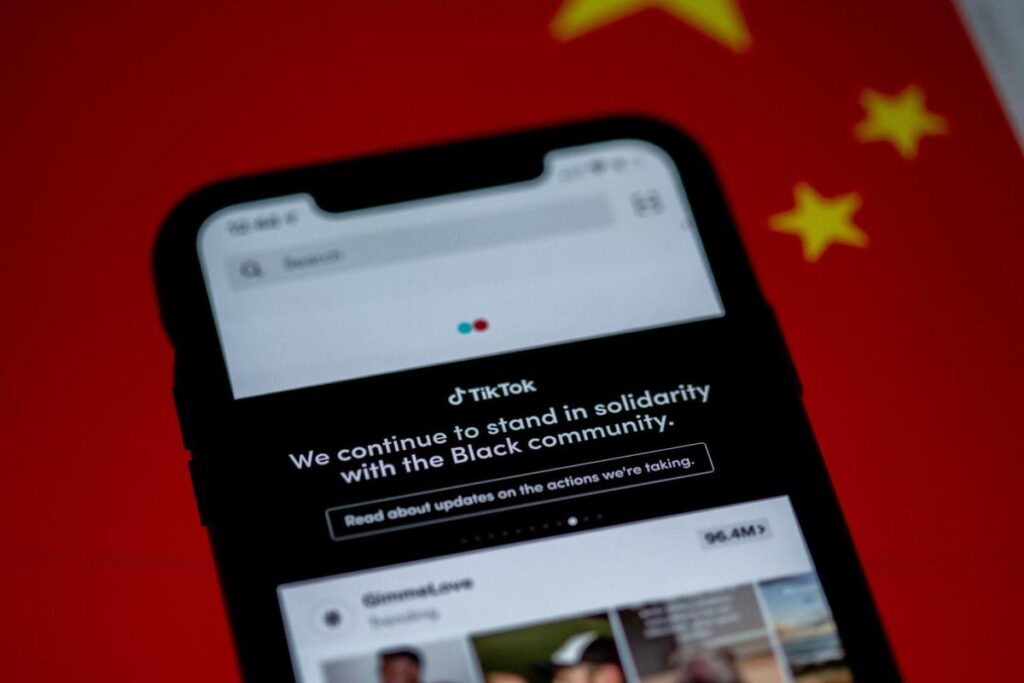

We discovered that the popular social media app TikTok is being used to spread disinformation and push content that breaches the platform’s terms of service, community guidelines, and even safety policies.

After analysing more than 500 TikTok videos, we found that 12% of the content contained deliberate attempts to misinform Ghanaians. Many clips we analysed contained overt misinformation and disinformation, with many containing violent and illegal activities, which directly go against TikTok’s terms of service, community guidelines, and safety policies. We also found many accounts and videos that specialised in spreading propaganda amongst Ghana’s TikTok users.

In today’s heavily siloed news environment, younger people are ditching traditional analogue and even digital information sources for social networks. Research by Google in the US showed that 40% of Generation Z, born in the 1990s or 2000s, who have grown up with the internet, now get most of their information from TikTok and Instagram.

Many users are aware of the pitfalls. UK regulator Ofcom noted that social media platforms continue to score worse than rival news sources on attributes, such as ‘trust’, with around two-thirds of UK users of social media sites saying they do not trust them for news.

Hosted by the Chinese company ByteDance, TikTok was originally devised for entertainment, inviting users to share short videos of ‘pranks, stunts, ticks, jokes and dance’. TikTok differs from other video-orientated platforms in that it only allows short clips, largely taken out of context. TikTok upped the time limit of its videos to 10 minutes in February 2022.

From music to militancy

With many users who have come to rely on TikTok to update them with a highly selective version of events, the site can foster regional and even global misinformation campaigns. The platform’s advertising reach in Africa is considerable: 27.8 million people in 2022.

Ghana TikTok, the umbrella term for one of the communities using the video platform, is a thriving space for the country’s youth, who became more politically active in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Spiralling prices and deepening inequality have fuelled disenchantment with the government. In 2016, only 28.4% of the Ghanaian population had access to the internet; by 2020, that figure was 53% of the population.

In 2020, the TikTok app had over 200,000 active users in Ghana, and the numbers are growing. At first glance, Ghana TikTok showcases the luxury lifestyle of the elite in Ghana, from high-end sports cars to glamorous mansions.

Of active TikTok followers in Ghana, 98.7% are 18-35 year-olds and they use the app for anything from news to discovering the latest Afrobeats artist. The app has influenced the Ghana music scene and becomes a promotional tool, creating a batch of new celebrities in the country.

Even so, the app’s popularity comes with risks, given TikTok’s potential for disinformation. A recent analysis of news related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine found that TikTok was a prime vector for spreading false narratives about the conflict.

As of December last year, 20 million users follow the #ghanapolitics hashtag, with an even larger 31.3 million people following #fixthecountry, a social media youth-based movement that advocates for freedom of speech.

By analysing more than 500 videos, The Africa Report sought to establish how far the social platform is shaping Ghanaian politics – and how much of the information being shared is truly factual.

Using popular hashtags on the site, including #fixthecountry, #ghanapolice and #ghanapolitics, as well as those of political parties and candidates, we discovered hundreds of videos on the platform had been taken from local television news stations. Often highly opinionated, these had been clipped to emphasise the punchiest phrases. This is not always outright disinformation, but can distort coverage when taken out of context.

In other videos, we found deliberate disinformation. Videos relating to other African leaders, such as Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari, were edited to appear as if they referred to Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo. Others, when analysed, were found to contain outright lies promoting hatred for rival political parties or ethnic groups.

Links to the dark web

There were also videos on the site that seemed to go unmoderated. These included videos that named and shamed teenage girls for sexual activities alongside photos of girls unconnected with them.

Videos of beatings and other horrific violent acts were also found during the investigation, some against young children. Many of these users promoted links to their sites on the dark web, for which they seemed to be cultivating many customers and followers on Tiktok.

TikTok is also a popular mouthpiece for political parties and opposition groups. Annan Perry Arhin, a member of the opposition National Democratic Congress’s communications team, has an active TikTok account with 26,500 followers. Whilst most of its content is pro-NDC news pieces, we found that some videos had been edited to change sources, which can mislead users.

Information is travelling faster, so it has given room for misinformation because of the low literacy levels […].

While the hashtag #FixTheCountry – the name of the civic youth movement mentioned earlier – has 31.3 million followers on TikTok, the organisation’s official TikTok account has only 141 followers. We asked Oliver Barker-Vormawor, #FixTheCountry’s convenor, why this might be.

“One of the difficulties we’ve had is the logistical work of TikTok compared to the other platforms because of their short videos. We are not in a position to fund some individual[s] to manage this full-time,” Barker-Vormawor says.

“Young people are emotive in their reaction, so they have a lot of time to cultivate that energy and direct it towards initiatives; but [disinformation] demobilises people to a point where nothing feels accurate and they think this is just propaganda.”

He warns that this can undermine activism, and “eventually, people will lose the energy that they need to be able to sustain civic initiatives”.

TikTok’s policies show some attempts to adhere to social-media good practices, including removing content or banning users that post hate speech or incitements to violence, and prohibiting ‘harmful misinformation’. It says: “We proactively enforce [our community guidelines] using a mix of technology and human moderation and aim to do so before people report potentially violative content to us.”

During the US elections of 2020, TikTok announced special measures for the US that included broadening its fact-checking partnerships, and “protect[ing] against foreign influence on our platform”.

Children at risk

In August 2021, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) released a report looking into digital misinformation and its impact on children and young people, who are often the target of online political campaigns. The organisation says: ‘The algorithms that are designed to serve up content that captures user attention and encourages sharing are also likely to promote misleading clickbait, conspiratorial rhetoric, and harmful mis/disinformation that endangers children, currently at marginal cost to content creators and technology companies.’

In 2014, the World Economic Forum identified the rapid spread of digital mis/disinformation as one of the top ten social threats, eroding public trust in facts, which shapes their ideas of politics and democracy. Between 2020 and 2021, fake news campaigns from ex-President Donald Trump were found to be one of the driving forces behind the Capitol Hill insurrection in Washington DC on 6 January 2021.

In Ghana, according to the 2021 Population and Housing Census, literacy rates in the country stand at 69.8%, with levels dipping as low as 32.8% in the Northern Savannah Region. Low levels of literacy may mean Tiktok users share content they may not fully understand or be able to identify as disinformation.

Kwaku Krobea Asante from Fact-Check Ghana, an outlet of the Media Foundation for West Africa, says the influx of new information into Ghana has led to more disinformation: “Information is travelling faster, so it has given room for misinformation because of the low literacy levels […]. You see a lot of people ‘misinforming’ and we need to distinguish it from disinformation. A lot more people [misinform] just because they do not have the knowledge.”

Ghana’s literacy rates, according to the 2021 Population and Housing Census, stand at 69.8% on average, dipping as low as 32.8% in the Northern Savannah Region. Low levels of literacy may mean TikTok users share content they may not fully understand or be able to identify as disinformation.

Smear campaigns

Ahead of the 2016 elections, Fact-Check Ghana started to combat what it calls “the proliferation of fake news, misinformation and propaganda, especially during electioneering campaigns, political debates, public health and other emergencies”.

A lot more people are looking to discredit their opponent and make them look bad whilst their case looks good, […] so they are concocting ideas for smear campaigns

Krobea Asante believes that the rise in disinformation is linked to political developments in Ghana, which have become increasingly unstable as the government battles growing debt.

“Before, social disinformation was intentionally sharing false information and setting targets, which is also brewing up because of this extreme politicisation and partisanship in our political landscape,” Asante says. “A lot more people are looking to discredit their opponent and make them look bad whilst their case looks good, […] so they are concocting ideas for smear campaigns.”

In a public letter addressing misinformation and “attempts to distort issues” in October 2022, the office of President Nana Akufo-Addo said it will “provide comprehensive responses to allegations made within the public domain within 12 hours of the allegation being brought to [its] attention”. The office also instructed ministers and other officials to “have an active social-media presence”, engaging with the public on various platforms.

With just under two years to go before Ghana’s next general election, there is time to train a serious light on the misinformation occurring on social media. In other African countries, the effects may already be far-reaching.

..

January 16, 2023 Published by The Dale Yeager Dotcom.