It’s an economist’s conundrum: global capital, instead of flowing from rich countries to poor countries, actually moves in the other direction. Each year hundreds of billions of dollars leave developing countries and land in the coffers of rich countries like Switzerland.

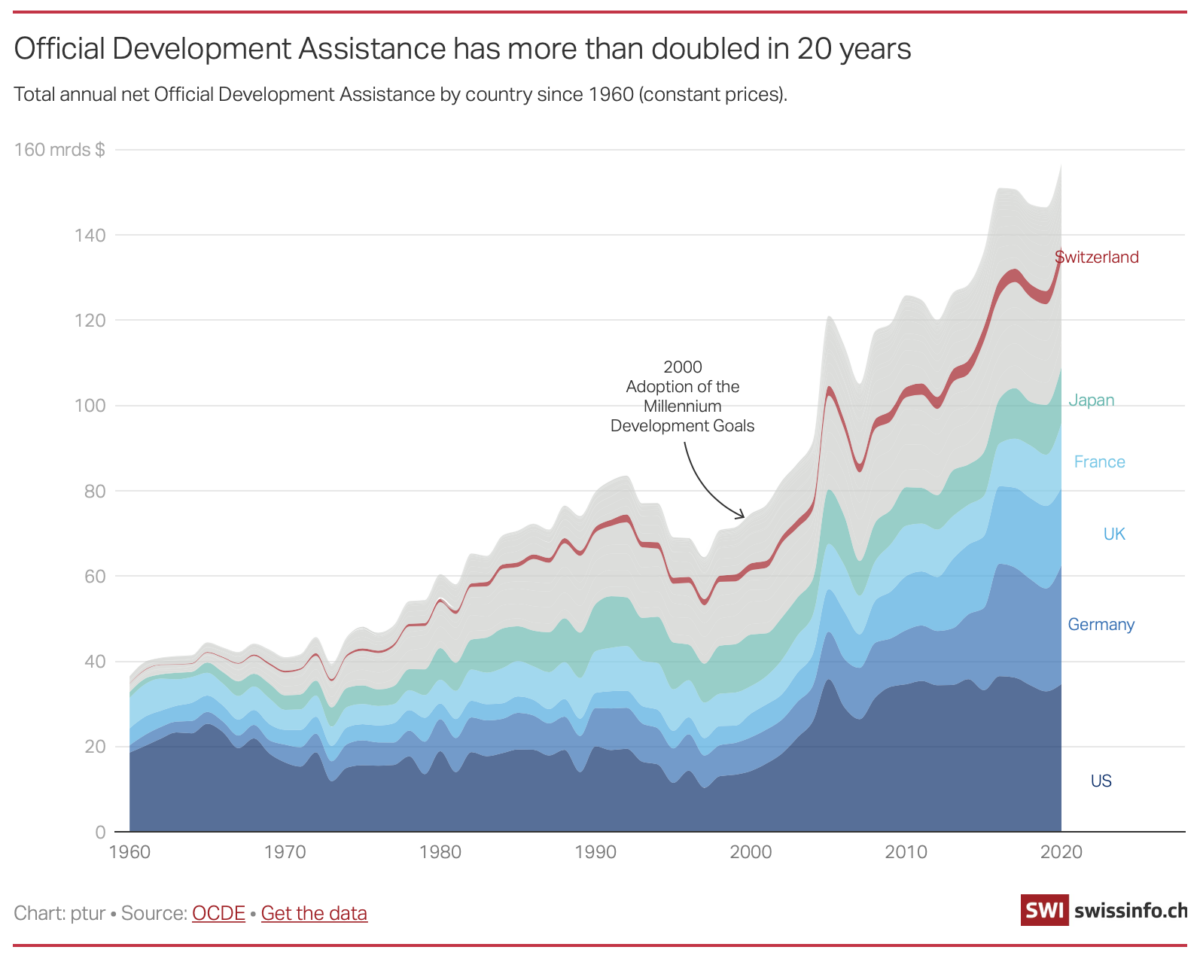

An “unprecedented” $160 billion (CHF149 billion) – about the same amount as the gross domestic product (GDP) of Hungary – was allocated last year by developed countries to Official Development AssistanceExternal link (ODA), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said in AprilExternal link.

With an average $120 billion spent each year, ODA spending has doubled since 2000.

.

.

But many experts caution that the dollar amount of development aid allocated by OECD countries obscures the fact that many of those countries, including Switzerland, do not do enough when it comes to their international commitments.

According to some, this could also lead to the perception that money flows in just one direction from donor countries to developing countries, when in fact rich countries rake in a good deal more of the financial flows coming from emerging economies.

.

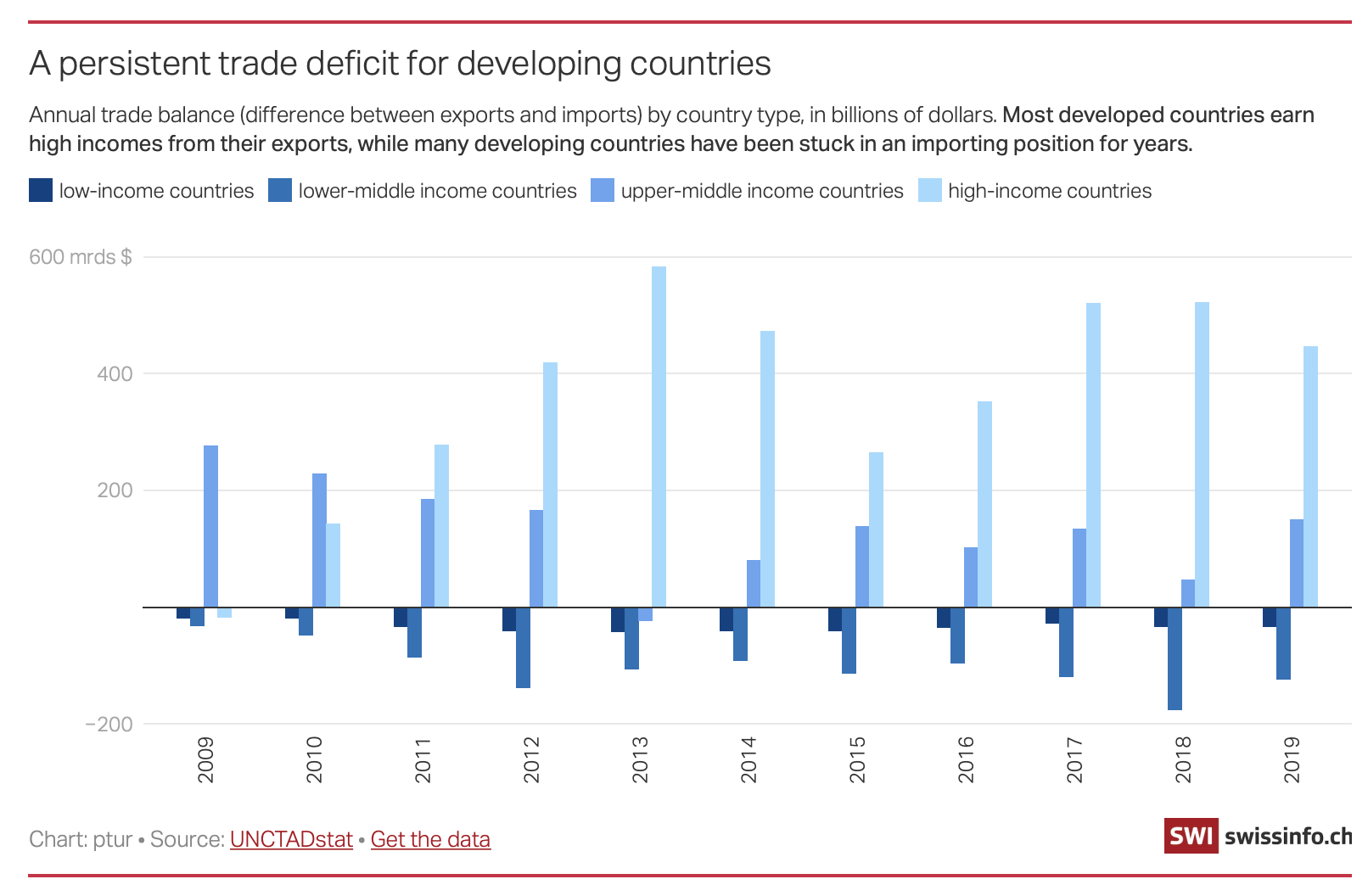

A persistent deficit

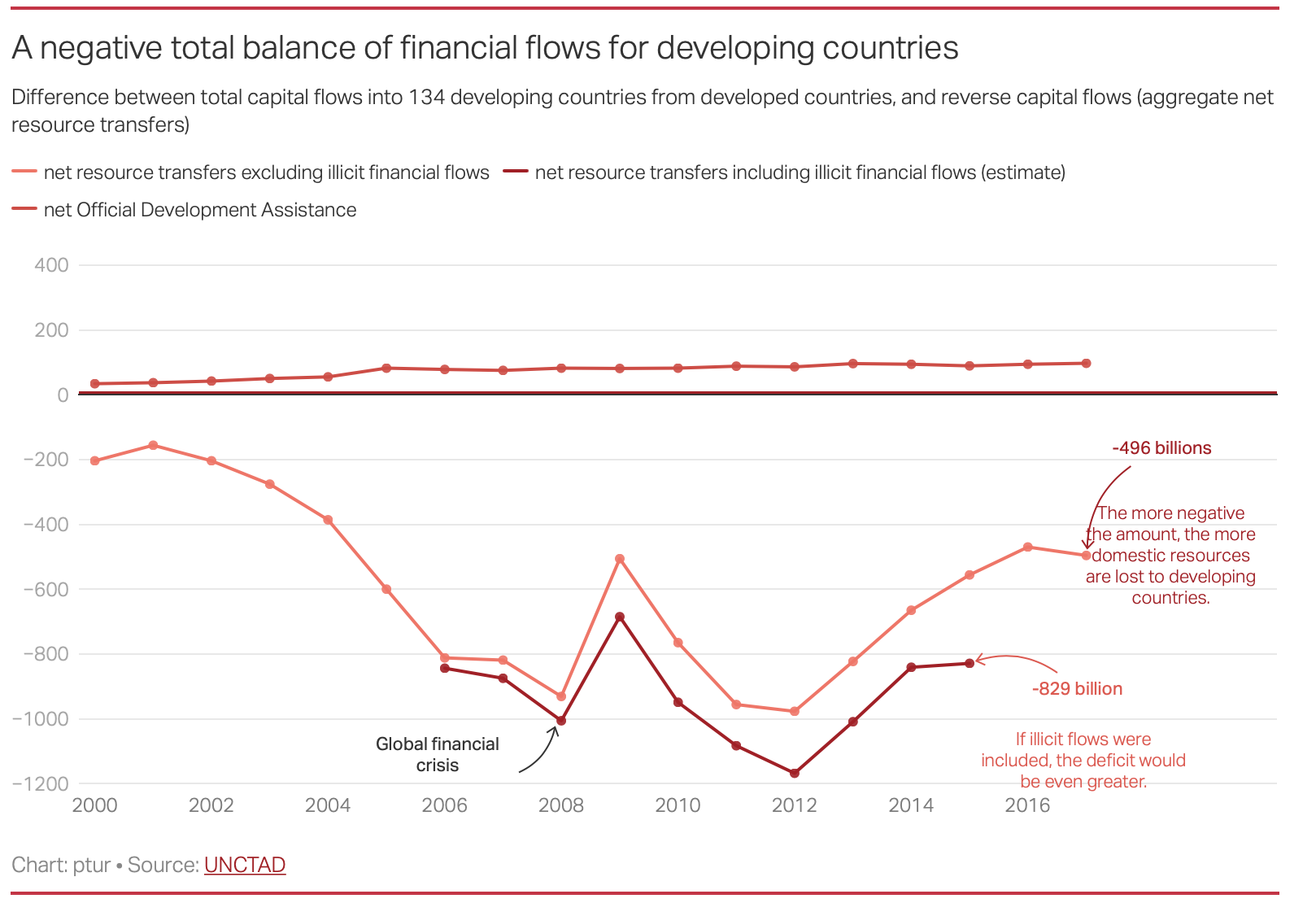

Rachid Bouhia, Geneva-based economic affairs officer with the division on globalisation and development strategies at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), says ODA spending is “minimal in view of the scale of the imbalance”.

In a policy brief published in May 2020, Bouhia noted that the total amount of financial flows leaving developing countries largely exceeds that which arrives from rich countries (whether from development aid, direct foreign investment, or trade).

.

This trend “contradicts the neoclassic economic theories, according to which capital should naturally circulate from rich countries to those lacking capital”, he explains.

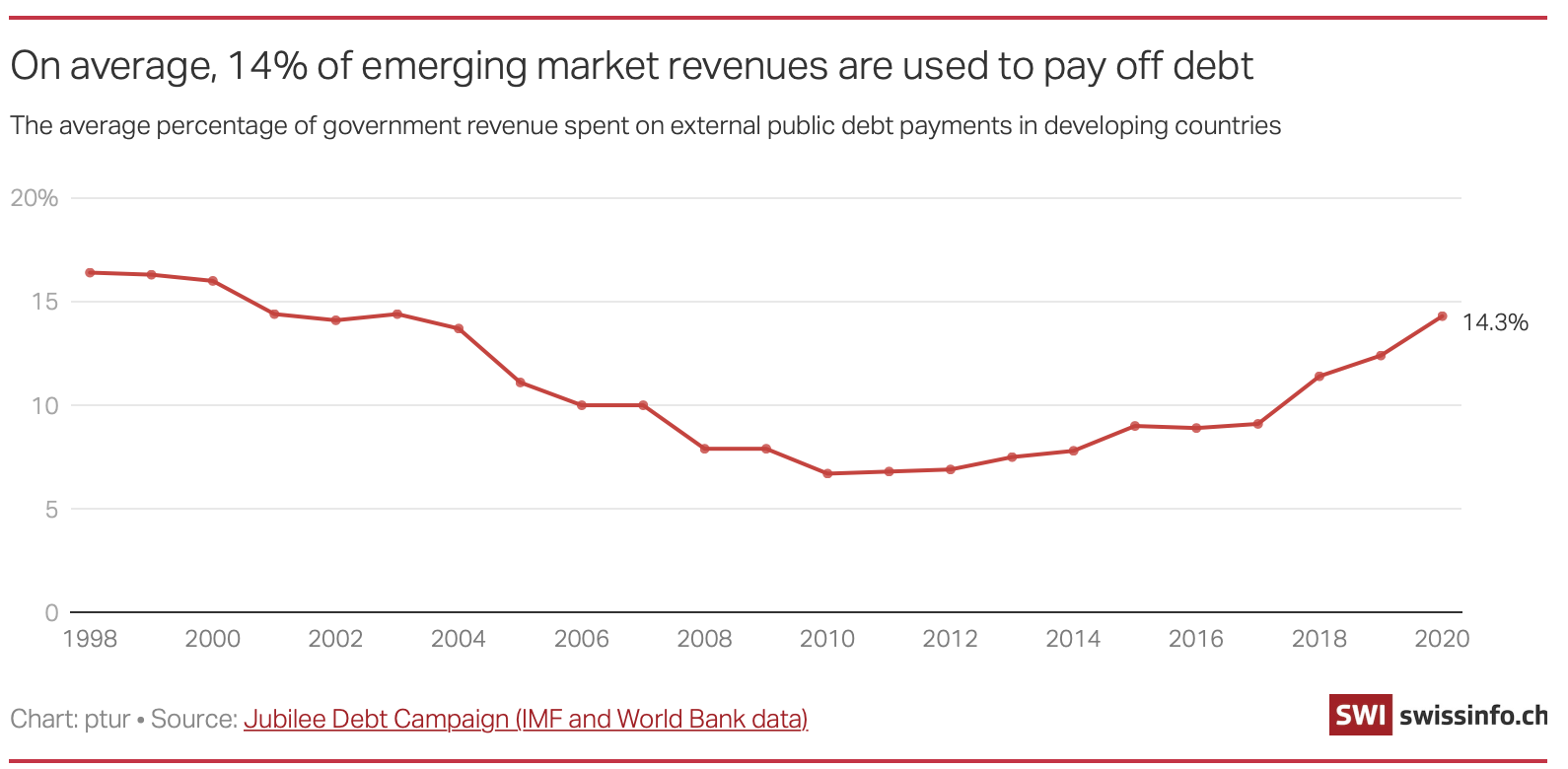

Capital flight results from several factors but is “closely linked to the financial fragility inherent in the external indebtedness of developing countries,” Bouhia writes.

Encouraged to seek foreign debt to finance development, some countries reach very high levels of debt that lead into a vicious spiral in which interest payments and profit transfers outweigh income.

.

.

Bouhia also points to the commercial trade deficit of several emerging countries which import more than they export, or which export raw materials that are subject to considerable cost fluctuations.

Finally, “to guard against risk, developing countries have embarked on a course of buying foreign currencies, in particular the dollar”, which amounts to an exit of capital from the purchasing country and a capital entry for the country whose currency it is.

.

.

Massive illicit flows

The official cumulative deficit for developing countries between 2000 and 2017 came in at some $11 trillion.

But these figures do not include illicit financial flows (IFF, added for illustrative purposes on the UNCTAD chart). Illicit financial flows include criminal transactions, money laundering, tax evasion and so on, but also legal trade “which is incorrectly invoiced […] with a view to tax optimisation”, explains Gilles Carbonnier, professor of development economics at the Graduate Institute Geneva.

By its very nature, it is impossible to put a precise figure on IFF. Tens if not hundreds of billions of dollars therefore escape any prospect of being allocated to development.

Faced with this set of facts, Liliana Rojas-Suarez, economist and emeritus collaborator at the Center for Global Development in Washington, cautions against drawing hasty conclusions. She says the aggregated methodologies reflect neither the individual situation of each country nor the complexity of exchanges.

Rojas-Suarez, who specialises in the links between financial flows and development, says it is important to look at the issue not only from a quantitative point of view, but from a qualitative one.

Investment, essential for development, requires large transfers of resources, she argues. When it comes to debt, “what is really important is to know if the borrowed funds were allocated to activities which create growth and jobs”.

This content was published on Oct 5, 2021Oct 5, 2021 The debate on decolonising aid is pushing Switzerland to question how it is approaching development work.

.

Finding a policy fix

Given that one symptom could lead to several diagnoses, the debate within international organisations over how best to rebalance the transfer of capital is a lively one. Rojas-Suarez believes priority should be given to the fight against illicit flows and strengthening transparency around loans between countries.

“The contracts should be published, we should know what the terms are so that we can determine if they really benefit the [developing] countries and do not expose them to over-indebtedness,” she says.

For its part, other than an increase in development aid, UNCTAD supports a form of protectionism as a means of enabling emerging countries to develop industry. It also wants greater controls over capital.

UNCTAD has also long called for the allocation of special drawing rights (SDR), an argument it finally won in late August when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced a record $650 billion investment in the global economy, of which $275 billion would go to developing countries.

Such measures, until now taboo in organisations such as the IMF, are starting to gain a foothold, says Bouhia. Has the pandemic finally shifted the goal posts?

.

By Pauline Turuban, October 11, 2021, published on SWI