European governments have frozen the Russian oligarch’s assets, including mansions and a soccer team. But how much he poured into the US has stayed secret. Between 2001 and 2016, a secretive network of 10 offshore companies plunged a whopping $1.3 billion into American investment firms and hedge funds.

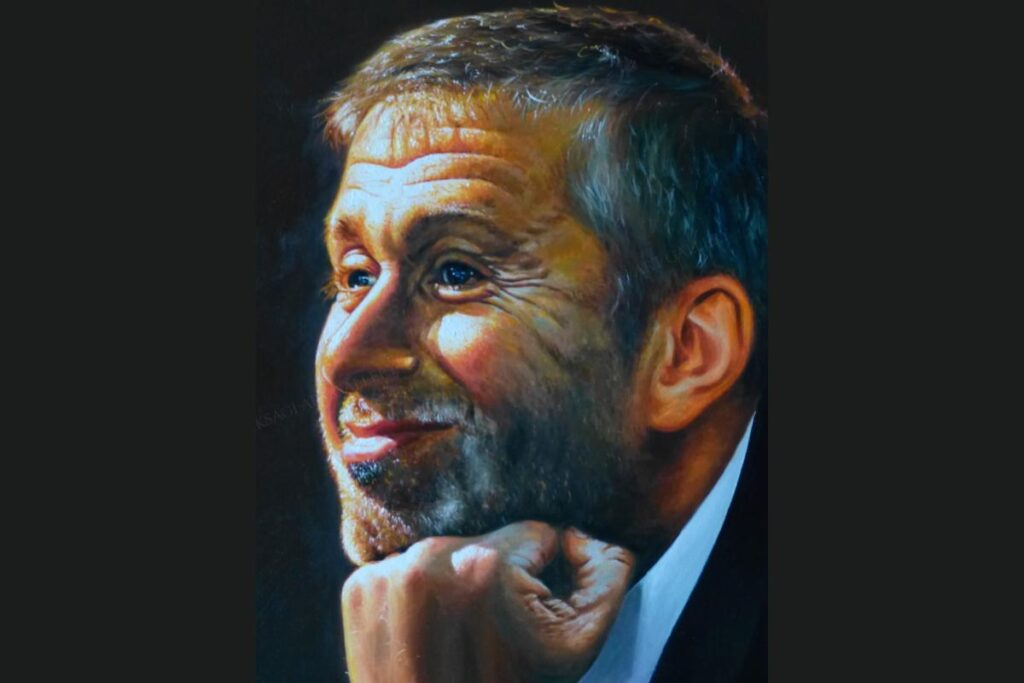

The money, sent through the high-secrecy jurisdictions of the British Virgin Islands and Cyprus, was difficult to trace. But with the help of confidential banking records, investigators at State Street, one of America’s oldest banks, stumbled upon the identity of the mystery investor: Roman Abramovich, the oligarch famous for his ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The investigators reported Abramovich’s investment network in a series of “suspicious activity reports” to the US Treasury Department in 2015 and 2016.

They pointed to court records showing that Abramovich had made “substantial cash payments” in Russia for “political patronage and influence.” And they detailed how the corporate structures of the companies holding the $1.3 billion had frequently changed, which they said could be an attempt to “conceal ownership.”

During the next six years, the US government took no action against Abramovich, and the State Street investigation stayed secret.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February, Western governments have moved to clamp down on oligarchs with ties to the Kremlin. Last week the United Kingdom sanctioned Abramovich, citing his “close relationship” with Putin and saying that materials from a steel company he controls may have been used to build Russian tanks. The UK froze his assets in the country, including several mansions and the Premier League soccer team Chelsea Football Club.

The US has not made any moves against Abramovich — but that may soon change, a US official told BuzzFeed News. Abramovich is under scrutiny by a new Justice Department–led task force called KleptoCapture, which aims to identify the wealth and freeze the assets of oligarchs who have aided Putin, the official said.

How much of Abramovich’s money made its way into the United States has never been publicly disclosed. The State Street investigation shows that Abramovich had invested as much as 10% of his estimated wealth into funds managed by American financiers.

.

.

Representatives for Abramovich did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The State Street episode, reported here for the first time, is based on the FinCEN Files, secret government documents obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Banks and other financial institutions send suspicious activity reports to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, known as FinCEN, when they spot a transaction that bears the hallmarks of money laundering or other financial misconduct. The reports are not evidence of a crime, but can be useful tools for law enforcement agents.

BuzzFeed News obtained thousands of these documents, which are never supposed to be made public, from Natalie Mayflower Sours Edwards, a whistleblower who worked at FinCEN. The Abramovich documents offer a hint of how much US investigators know about his holdings — and raise questions whether the government holds similar information about other oligarchs close to Putin.

Abramovich has long been an object of controversy. In the turbulent 1990s, as Russia transitioned from Soviet communism to cartel capitalism, he made billions snapping up state energy companies on the cheap in rigged deals as they were privatized. Abramovich’s own lawyer has accepted in a British court that Abramovich was privy to corruption during this time.

This did not prevent him from receiving a warm welcome in the West — especially the UK. In the early 2000s, he bought Chelsea Football Club, as well as a swath of luxury properties in London’s upscale West End. He was such a fixture of “Londongrad” — the nickname for a city famed for its open welcome of oligarchs — that he was even parodied in a Guy Ritchie film.

In mainland Europe, Abramovich had other luxury properties, including a mansion on the French Riviera once inhabited by King Edward, who abdicated from the British throne in 1936. The oligarch’s yachts were frequently moored in the Mediterranean.

.

“People knew who Concord was and they knew he was part of it, and there may be cases where his name is on paperwork.”

.

Abramovich acquired a reputation with the British press for using expensive lawyers and the country’s strict libel laws to defend his reputation. While journalists and politicians occasionally questioned the source of Abramovich’s funds, his wealth was left untouched by Western governments even as relations with Russia soured through the 2010s, as Putin’s government invaded eastern Ukraine, interfered with elections, and used a nerve agent to poison the defector spy Sergei Skripal in a small English town.

That ended when Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Two weeks after Russia fired the first missiles, the British government sanctioned Abramovich, citing his decadeslong “close relationship” with Putin. “This association has included obtaining a financial benefit or other material benefit from Putin and the Government of Russia,” the British Treasury said. The European Union announced its own sanctions against Abramovich on Tuesday.

But while Abramovich’s rise and fall in Europe is well documented, little is known about his dealings with the American financial system. The suspicious activity reports filed by State Street shed light on Abramovich’s decadeslong move into the American financial system, with the helping hand of US investment firms. (Disclosure: State Street bought a stake in BuzzFeed in 2021.)

State Street did not itself handle any of Abramovich’s money. One of the bank’s divisions had a contract to work for hedge funds, managing their client files and performing anti–money laundering checks. Hedge funds make their money by taking cash from wealthy investors and investing it on their behalf. The cash itself may be invested abroad, but the money is managed from the US.The bank’s investigation started after the Wall Street Journal reported that US authorities were probing whether hedge fund Och-Ziff knew about a loan that a company it invested in had made to Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe.

As they looked at Och-Ziff’s roster of clients, the State Street investigators discovered the network of 10 offshore companies, based in the British Virgin Islands and Cyprus, that held $1.3 billion in investments in various funds. American banks are required to report any suspicious activity they detect to the US Treasury Department, so the State Street investigators started digging.

One of the companies in the network, Netherfield, was involved in a complex offshore transaction that raised $50 million for a company controlled by Igor Shuvalov, one of Putin’s key advisers. The deal was reported in Barrons in 2011. The story did not name Abramovich as the owner of Netherfield, but the State Street investigators ultimately found that it belonged to him. In the months after the story ran, Netherfield was closed down, and its investments were moved to a newly formed company in the British Virgin Islands, the State Street investigators found.

Cash used for the network’s investments came from accounts at a small commercial bank in Austria called Kathrein. But when some investor accounts were set up, Kathrein did not name Abramovich as the ultimate owner of the money on any documentation. Kathrein did not comment on this story, citing Austrian bank secrecy laws.

A firm called Concord Management appeared to have been set up to oversee the investments. Yet State Street had trouble finding basic details about Concord — including whether it even existed.

Investigators were “unable to identify or verify the existence of CONCORD and the entity has a non-functional website,” they wrote in one suspicious activity report. “Several of the individuals named as contacts have a limited internet presence.”

“Additionally, the address provided for CONCORD … is a commercial office park.”

In a statement sent to BuzzFeed News, a spokesperson for Concord Management said the company “provides independent third party research, diligence and monitoring of investments, but does not invest in any funds.”

In the end, the State Street investigators reported Abramovich, his offshore companies, Concord Management, and Kathrein Bank to the Treasury for suspicious activity in December 2015.

They also noted that Och-Ziff and several other American investment funds, including BlackRock, had counted Abramovich’s offshore companies among their clients. State Street did not name those funds for suspicious or criminal activity, and there is no evidence that they acted against any financial regulations or laws.

Representatives for BlackRock and for Och-Ziff, now rebranded as Sculptor Capital Management, declined to comment on Abramovich. “BlackRock has a robust compliance program, abides by all applicable regulations, and takes the necessary steps to ensure adherence with relevant sanctions,” a spokesperson said. None of the funds commented on whether Abramovich remains a client, though some US investment companies have frozen his cash.

One employee at a fund that worked with Abramovich said that all the transactions were legal at the time, and that it was no secret in financial circles that Abramovich was investing in the US. “People knew who Concord was and they knew he was part of it, and there may be cases where his name is on paperwork,” the employee said. “There’s a dynamic where he is retroactively toxic in some people’s minds.”

In March 2016 State Street followed up with a series of additional suspicious activity reports offering further details about the bank’s ongoing investigation. The bank said it had halted a number of transactions linked to Abramovich’s offshore network until investigators had received documents showing how the companies were linked to Abramovich. The bank had been asking Abramovich’s advisers in the UK for paperwork detailing how he owned the companies.

Once those documents arrived, the money continued to flow. Investigators watched as Abramovich restructured his investments into new companies owned by an offshore trust that, they wrote, “allows RA to anonymously own/control the entities.” The bank said it was concerned that the moves “further serve to distance RA as the source of wealth and beneficiary of the assets.”

In the UK, Abramovich’s assets are now frozen. His properties, including a £125 million mansion in Kensington Palace Gardens, are in limbo.

So too is Chelsea Football Club, which has to operate under tight government controls to ensure Abramovich does not receive revenue from the club. Season ticket holders can still attend games, but the club is not allowed to sell any new tickets. Its millionaire football stars may have to stay in budget hotels for away games. Business owners across the world are lining up bids for Chelsea, which was once Abramovich’s most prized Western asset. The UK government has reportedly said that the proceeds of any sale would not go to Abramovich.

When or how American authorities might act remains unclear. Political pressure has been ramping up: Last week, three Democrats in Congress sent a letter to President Joe Biden urging him to sanction Abramovich, saying “U.S. sanctions against Abramovich are conspicuous by their absence.”

“I’m not sure why the US hasn’t acted yet,” Rep. Steve Cohen, a Democrat from Tennessee, told BuzzFeed News. “I understand we may need to act in concert with our allies, but in this instance we seem to have been late to the table.”

Meanwhile, Abramovich’s more mobile assets have moved away from the West. His yachts left European ports for the open sea, and his jets have flown to Russia and Istanbul.

Abramovich was once a familiar figure in the director’s box at Chelsea, but at the moment it is unclear where the enigmatic oligarch is. He was last seen in the luxury lounge of Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv with a mask on his chin. He reportedly flew to Turkey, or maybe Moscow.

.

March 16, 2022 Published by The Buzzfeed News.