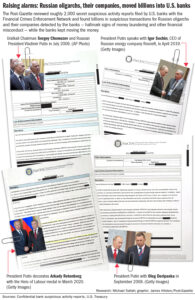

U.S. banks were warned by their own employees, but moved money anyway for oligarchs’ companies. Arkady Rotenberg emerged as one of Vladimir Putin’s most trusted allies, a former judo partner who reaped billions in government contracts and insider deals and became one of Russia’s most influential oligarchs.

Igor Sechin was a Russian deputy prime minister who was tapped by Mr. Putin to take over the state oil company and is considered by many to be the second most powerful person in Russia.

Sergey Chemezov was a onetime KGB agent and top general who was appointed by the Russian president to head the nation’s massive defense conglomerate.

As they rose in power, they followed a common path: They used the American financial system to move their wealth – billions of dollars that poured into U.S. banks in patterns that set off alarms among the bank experts charged with detecting financial crimes.

Time and again, some of the largest and most recognized financial institutions opened their doors to a cadre of Russia’s oligarchs — now the targets of sweeping sanctions in the wake of Mr. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine — while they transferred their money in a relentless flow of dollars.

A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette investigation, bolstered by thousands of secret government records, found that banks kept moving billions for the oligarchs and their companies at the same time they were filing reports with the U.S. Treasury after they found the hallmarks of financial crimes like money laundering.

Known as suspicious activity reports, the records — which are never disclosed to the public — are part of a Post-Gazette investigation into money laundering that began with revelations about millions of dirty dollars in the U.S. steel industry.

The records, shared with the newspaper by BuzzFeed News reporter Jason Leopold, offer an extraordinary glimpse into the world of international corruption, terrorist networks, and the global elite who move their money through American banks.

.

Russian President Vladimir Putin decorates businessman Arkady Rotenberg with the Hero of Labour medal during an awards ceremony in Sevastopol, Crimea, on March 18, 2020.

Consider the case of the 70-year-old Mr. Rotenberg, whose companies reaped billions to set up the Winter Olympics in Sochi eight years ago and whose holdings include four villas and a luxury hotel in Italy, according to Forbes.

Societe Generale’s New York office filed six suspicious activity reports starting in 2012 that raised alarms about millions of dollars transferred from shell companies that he secretly owned and were registered in the Caribbean.

Despite the concerns, the bank moved the money to the companies, some involving his son and brother, Boris, with the bank unable to verify why the funds were being exchanged.

In one transaction, the bank moved $94 million from a company registered in the British Virgin Islands — one of the foremost havens for financial secrecy — and owned by the oligarch, to a company tied to Sergei Roldugin, another friend of the Russian president.

The reason for the payment: a loan deal to buy a Russian telecom company, the bank said in a 2016 report.

After years of moving millions through U.S. banks, Mr. Rotenberg and his brother were barred from the financial system after they were sanctioned when Russia invaded Crimea in 2014.

But it didn’t stop them: The brothers kept moving funds into the U.S. through shell companies, this time to buy expensive artwork through a buyer — $18 million for pieces at Sotheby’s in New York and from a private dealer, said a Senate report in 2020.

A representative for the brothers said at the time they did not violate any laws, but Senate investigators said the purchases were carried out to conceal their money and evade sanctions.

.

.

Russian power brokers

By themselves, the bank reports are not evidence of a crime, and no charges have been filed by law enforcement against the people named in the records.

But the findings raised enough alerts among internal experts at the banks to pursue their own inquiries and send the reports to the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

Sanctions imposed over the last several months are designed to ban the oligarchs from a U.S. financial system that’s critical to international businesses and serves as a haven for investors from countries with shaky currency systems.

But for years, the Russian power brokers and the banks benefited from each other, with the billionaires sending money into the U.S. while the banks reaped profits from the dollars parked in their coffers.

The movement of money illustrates the ease with which the oligarchs — a group accused by the U.S. government of corruption — have gained access to the banking system, despite the responsibility of banks to block the flow of shadowy funds.

.

.

In a written statement to the Post-Gazette, Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, who chairs the Senate Finance Committee, said the findings are troubling and “make it clear there is still much more to be done, especially by banks and those who regulate them, and by law enforcement — to ensure that suspicious activity is investigated and, where appropriate, shut down and prosecuted.”

The suspicious activity reports show that large amounts of the money belonging to the oligarchs and their companies flooded the U.S. financial system from shell companies in such places as the Cayman Islands, Latvia and Cyprus, long known as offshore tax havens.

The newspaper reviewed roughly 2,000 such reports filed by the banks under a law that compels the institutions to report suspicious dollars to the government.

.

“It’s willful blindness. ‘I don’t want to know about it … I want to make money.’”

— Thomas Nollner, a former regulator for the Office of Comptroller of the Currency

.

While banks are empowered to refuse the transfers and drop the customers, records show that in more than four dozen suspicious cases between 2011 and 2017 involving now sanctioned Russian oligarchs and businesses, only three transactions were rejected.

.

The money trail

The Post-Gazette spent a month reviewing thousands of highly confidential suspicious activity reports filed by the banks and searching for the names of individuals and companies currently under sanctions since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This included writing custom computer code to extract primary pieces of information from each report and assist with the searches.

During that process, the Post-Gazette found numerous individuals and companies who had been previously sanctioned since Russia’s initial annexation of Crimea in 2014, as well as those sanctioned more recently.

The individuals include: Oleg Deripaska, Arkady Rotenberg, his son, Igor Rotenberg and his brother, Boris Rotenberg, Sergey Chemezov, Igor Sechin, Gennady Timchenko, and Alisher Usmanov.

The companies and banks include: Basic Element Limited, NPO Mashinostroyenia, Surgutneftegas, Rosneft Oil, SMP Bank, InvestCapitalBank, Inresbank, Bank Rossiya, Sobinbank, Vnesheconombank, Sviaz-Bank, Globexbank, The Central Bank of the Russian Federation, VTB Bank and Sovfracht.

In the vast majority of the transfers tracked by the Post-Gazette, the sanctioned subjects were not direct customers of the US banks, but utilized the US banks to move their money.

Under law, those banks that transfer money into the US financial system – known as correspondent banks – are required to screen for suspicious activity such as money laundering.

In all, the Post-Gazette tracked tens of billions of dollars in transfers on behalf of eight oligarchs, their companies, and 15 Russian banks and other businesses — all now under sanctions.

.

‘Banks have to say no’

“The result of these actions by the banks is that the U.S. as a country opens up its doors to corruption and criminal money,” said Ross Delston, an attorney and former regulator at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. “They have to be able to say no.”

The transactions took place as some banks — including Deutsche, Bank of New York Mellon and Societe Generale — had already been in trouble with the Justice Department and other government agencies over financial misconduct and anti-money laundering violations.

In the case of Deutsche, the largest bank in Germany with nearly $2.8 billion in profits last year, the bank paid a $425 million fine to New York state regulators in 2017 and admitted its efforts to stop money laundering were weak and seriously deficient and needed to be improved.

In response to questions from the Post-Gazette, Deutsche and Bank of New York Mellon said in emails the banks work with authorities to protect the financial system, but were unable by law to comment on the suspicious activity reports.

Deutsche Bank “has substantially reduced its Russian exposure since 2014,” and the bank is “in the process of winding down our remaining business in Russia while we help our non-Russian multinational clients in reducing their operations. There won’t be any new business in Russia.”

Societe Generale declined to comment.

Under the law, banks are supposed to be the first line of defense in the war against money laundering by screening their customers and filing reports when they suspect financial wrongdoing.

When it comes to the oligarchs — accused of profiting from a corrupt regime — the banks should be regularly monitoring their money, said Mr. Delston, a longtime expert witness in money laundering cases.

“They are from a high-risk country and they have close ties to Vladimir Putin. Those two facts alone should be enough to be considered the highest risk-rating applied to that customer,” he said.

At times, the banks conducted inquiries well after suspicious money had already breezed through their systems.

.

Russian tycoon Gennady Timchenko attends a meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and French businessmen at the Kremlin in Moscow on May 25, 2016.

.

The Putin connection

Weeks after a Wall Street Journal story reported that Gennady Timchenko and his business were under a federal money laundering probe, Deutsche launched a review of transactions for his oil export company in 2014.

Prompted by the allegations, the bank said it turned up 335 transactions for the Gunvor Group in the prior three years and found no information to show the legitimacy of dozens of transactions amounting to $152 million.

Mr. Timchenko, 69, who was not charged in the probe, had been sanctioned eight years ago and was hit with measures again by the State Department last month along with his wife and two daughters.

In the case of oligarch Igor Sechin, Deutsche bankers found dozens of large, round dollar transactions along with money from high-risk countries and no information to support the purpose for millions in transfers.

A former KGB officer and deputy prime minister of Russia, Mr. Sechin, known by the nickname “Darth Vader,” is considered to be Mr. Putin’s closest confidant and is the CEO of Rosneft, the largest oil producer in Russia.

In the course of its investigation in 2015, the bank said it found suspicious payments ranging from a single dollar to $1 billion in the previous four months.

Thomas Nollner, a former regulator for the Office of Comptroller of the Currency, said most U.S. banks moving funds for Russian billionaires are driven by the fees that are generated — and the profits.

“It’s willful blindness,” said Mr. Nollner. “They want the money — the income they get from it.”

U.S. Banks are supposed to ask the foreign banks sending the funds to turn over information if they suspect wrongdoing, such as the names of clients or the legitimacy of the payments, said Mr. Nollner.

.

An FBI agent guides a tow truck as it arrives to remove a vehicle from the home of Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska in Washington, D.C., on October 19, 2021..

.

Explosive stories

At least 11 times, Deutsche’s fraud experts reached out to Sberbank — Russia’s largest financial institution — and asked about the purpose of payments between companies from 2011 to 2014. And each time, Sberbank refused, saying it could not comply because of Russian law.

Though Deutsche could have stopped the transfers — which included nearly $7 million from a firm controlled by oligarch Oleg Deripaska — it kept moving the money.

Mr. Delston, the former regulator, said it’s unclear if the funds are illicit, but the “risk rose up dramatically” when the bank chose to move the money without basic questions being answered.

“Banks don’t take risks seriously until there is some outside event — indictments, publicity, sanctions,” he said.

An explosive series of stories in 2016 led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists about some of the world’s richest people hiding their wealth in offshore havens prompted Societe Generale to review the finances of Mr. Rotenberg.

As part of the telecom deal, the bank found it had carried out additional transfers for $91 million from two shell companies set up in the British Virgin Islands in 2013 and owned by the oligarch, who amassed a fortune in state contracts during the Putin presidency.

That money was sent to the shell company tied to Mr. Putin’s friend, Mr. Roldugin.

In the ensuing years, Mr. Rotenberg and his brother Boris were targeted in the Senate investigation and their finances were exposed, but they continued to reap government benefits in Russia. In 2019, a company owned by Arkady Rotenberg received a state contract for $688,000. The reason: To conduct anti-corruption training.

In the latest round of U.S. sanctions, both brothers were slapped with visa restrictions, along with members of their families.

.

Head of Russia’s Rostec state conglomerate Sergei Chemezov attends a ceremony in the military Patriot Park outside Moscow on August 23, 2020.

There is also the case of Sergey Chemezov, one of the Russian president’s closest insiders who was first sanctioned after Russia invaded Crimea and whose super yacht worth $140 million was seized by Spanish authorities last month.

Deutsche Bank filed at least nine suspicious activity reports in just two years raising alerts about transactions involving his company, Uralkali, the massive Russian fertilizer supplier, a 2017 report said.

.

‘Shut it down’

Despite warnings from the bank’s own workers, Deutsche kept moving the money — billions of dollars — even though the bank was unable to determine the legitimacy of some of the payments or why they were made between companies with no discernible business relationships, records show.

Mr. Chemezov, who once served in the KGB with Mr. Putin in Germany, has been banned from entering the U.S. along with his wife, son and step-daughter by the State Department in the latest round of sanctions.

Paul Pelletier, a former federal prosecutor and Justice Department fraud unit chief, said at some point, the bank should have rejected the money rather than merely writing report after report.

“Why do you keep filing the SARs? Shut it down,” said Mr. Pelletier, who once led prosecutions of laundering cases in Miami. “Shut them out of the banking system. Otherwise, you’re just money laundering if they are proceeds [of a crime].

Year after year, U.S. banks moved billions for companies controlled by Oleg Deripaska, a Kremlin-linked oligarch who emerged during the free-for-all economy that followed the fall of the Soviet Union to oversee one of the largest aluminum empires in the world..

.

Russian tycoon Oleg Deripaska in June 2021.

His business ties with Paul Manafort, the former campaign manager for former President Trump, led him to become an early focus of the U.S. investigation of Russian meddling in the 2016 election, but that waned after investigators found no evidence of coordination between Mr. Trump and the Russian government.

Before the U.S. Treasury sanctioned Mr. Deripaska in 2018, Deutsche and Bank of New York Mellon spent years moving money for his companies — even while they filed reports saying many of the transfers looked highly suspicious.

At least as far back as 2009, Deutsche Bank shot up alarms that it suspected money laundering involving a company under the oligarch, but continued whisking the dollars through the bank.

At least seven other suspicious activity reports followed over a 21-month span, all raising concerns about allegations against Mr. Deripaska of laundering and ties to organized crime.

The bank noted that the flow of money prompted alerts because of unusual variations and large, round-dollar amounts. But the transfers kept coming — nearly $1.7 billion.

It was the same with Bank of New York Mellon.

In a 2015 report to the Treasury Department, for instance, the bank flagged 250 transfers for more than $56 million. The bank’s experts said the transactions – involving “shell-like entities in high-risk jurisdictions” such as Russia, Cyprus and Bermuda — benefited Russian oligarchs, including Mr. Deripaska.

The bank noted that offshore companies with no known ownership “are a concern for money laundering and financial crimes given that they are easy to form, inexpensive to operate, and are structured in a manner designed to conceal the transactional details of the entities.”

The 54-year-old oligarch denied any wrongdoing during a legal challenge to his sanctions, but his efforts to lift the measures were rejected by a federal appeals court last week.

.

Russian oligarch Alisher Usmanov in November 2008.

.

Warning after warning

For Alisher Usmanov, a mining magnate and one of the richest men in Russia, it was a government request to Bank of New York Mellon that prompted the bank to drill down on one of his investment companies.

The inquiry led to an examination of 16 years of transactions involving Gallagher Holdings Ltd., registered in Cyprus.

Despite warning after warning — money sent to suspected shell companies; money moved in large, round numbers; no clear signs where the funds were coming from — the bank kept carrying out transactions for his company.

In all, the bank’s fraud experts turned up 182 suspicious transfers amounting to $1.68 billion for the company, a 2016 report stated.

.

“They are from a high-risk country and they have close ties to Vladimir Putin. Those two facts alone should be enough to be considered the highest risk-rating applied to that customer.” — Ross Delston, former regulator for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

.

Another red flag: links to the Russian president. Gallagher Holdings, the bank wrote, “appears to be owned by individuals with connections to Putin…”

Mr. Nollner said the bank should have been routinely screening its database for money coming from Russia for people who are part of Mr. Putin’s inner circle.

The Post-Gazette found that in at least three cases, the banks didn’t carry out suspicious activity inquiries until months after sanctions were imposed.

“Every bank should have a practice in place to review sanctions every day,” he said. “It’s common damn sense. Why were you not watching this person closer?”

Mr. Delston, the lawyer and former bank regulator, said ultimately the impact on the country is not just measured by the money flowing into the banks.

The deficiencies open the door to organizations that go beyond the oligarchs and Russian businesses at the center of the U.S. sanctions, he said.

“It’s a free ride to invest the proceeds of financial crime,” he said. “It lets them know that they can keep the proceeds. There are really bad things that happen when illicit funds flow into the United States, being a safe haven for the world’s criminals and corrupt politicians. That’s not a good thing for this country.”

.

April 3, 2022 Published by The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.